SERIOUSLY. This is what the crap Hollywood still puts out?

View Morebrilliant actors, brilliant editing

Absolutely brilliant

Great example of an old-fashioned, pure-at-heart escapist event movie that doesn't pretend to be anything that it's not and has boat loads of fun being its own ludicrous self.

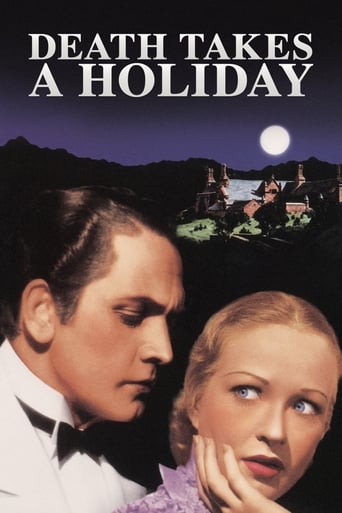

View MoreIn this fantasy film directed by Mitchell Leisen, the grim reaper (Frederic March) gets a reprieve from his duties for three days, and he's also allowed to take human form. Over the ages he's seen life in all its smallness, and can't understand what makes living so special, or why people fear him. He comes primarily seeking knowledge, but soon finds himself enjoying new experiences and emotions. I enjoy films where Death is a character, and this one is an interesting mix of philosophy, fantasy, humor, and romance. The premise allows the film to explore the nature of life and love in fundamental ways. We see this early on as Death raises a toast and says "To this household, to life, and to all brave illusion." As we smile at his enjoyment over tasting wine and feeling its effects for the first time, we understand that from a higher, eternal perspective, all of what we do is indeed a 'brave illusion'. Now it turns out that if Death is taking a holiday, no one else receives him as a visitor, and we see news reports of people not dying during fires and other accidents. Death enjoys himself, but remarks that people seem to spend too much time indoors, and says "I have been among you two days, and what you do with yourselves still seems so very futile and empty." He also makes this devastating comment on war: "I could never make out what it was they were fighting about. It's usually a flag, isn't it? Or a barren piece of ground that neither side wants." What a fantastic line, so touching in any era, and particularly meaningful in the interval between WWI and WWII. It helps set up another observation from Death, relayed by Henry Travers (yes, Clarence from 'It's a Wonderful Life'): "Has it ever occurred to you that death may be simpler than life, and infinitely more kind?"If all this sounds gloomy or Bergmanesque, it's really not. There is one frightening scene where he reveals himself to a young woman, but overall the film is lyrical and reasonably light, and in fact it feels a bit theatrical in places. The story shows us that love is what ultimately transcends the absurdity of our brief existences. What starts out as a comedic competition with Gail Patrick and Katharine Alexander vying for Death's affections, evolves to Evelyn Venable and Death falling for one another. There is a lot behind these lines which he utters, and anyone who has fallen hopelessly in love will identify:"A moment ago I knew only that men were dust, and their end was dust. And now suddenly I know for the first time that men bear a dream within them... a dream that lifts them above their dust, and their little days. And you have brought this to me. I look at the stars in the water, Grazia, and you have given them a meaning."Essentially, the film asks the question, what if love "were only a few days or a few hours, would that be enough to justify love?" The ending, while a bit melodramatic, answers in the affirmative. True love not only what gives life its meaning, but it's also more important than life.

View MoreHere is the biggest "spoiler" this review is going to offer: ignore the remake. Yes, I know the remake has Brad Pitt and Sir Tony Hopkins and about (it seems) a 6-hour run time - yawn - whereas this poor original, in contrast, "only" has Frederick March and about an 80 minute run time and special effects from the 1930s. Seems no contest? It is. Ignore the modern version, it is junk. See this, the original, based very closely on the original stage play, with March giving one of the best performances of this career (by the 1950s, some 20 years later, this great actor, with a mesmerizing physical presence, was reduced to B movies. Same thing happened to Rita Hayworth). The story is a one-of and as far as this reviewer is concerned, un-equalled even today. Death gets bored, wants to experience physical life, wants to experience love. Takes the form of a visiting prince at a gathering of upper class wealthy types (in films and plays of that era, the upper class were always visiting each other or partying or philosophizing). After warning his host not to reveal his true identity, Death in human form tries to mingle. And that's all the spoiler you get. Astonishing writing, deft dialogue, an odd mixture of horror story, love story, and suspense story. I would without hesitation call this one of the best 100 films of all time, and my reviews here show that I have seen my share to judge from.

View MoreThis fascinating curio from the 1930s is based on an Italian stage play that posited the simple question: Would Death be intrigued by why we mortals cling so stubbornly to life in spite of our self-evident self-destructive urges. Death, in this movie, is at a disadvantage in this since he is immortal and can never death itself. It posits a question that has been posed as earlier as the ancient Greek playwrights such Euripides: Are the gods inferior to mortals because the former have no knowledge nor capacity for understanding the deep suffering the latter are capable of because mortals are always aware on some level that they will ultimately die? This story, Death Takes a Holiday, is reminiscent of aspects of Christian theology that posited Jesus, as the Son of God, was part of the divine Godhead and thus by allowing Jesus the Crucifixion, God could come to understand the suffering of which His creation was capable. By that understanding, Jesus could redeem the sins of mankind as God, through Jesus, gained an understanding of what it meant to be human. Even though this perspective isn't strictly orthodox, it was best illustrated in another movie, The Green Pastures, which was made in 1936.As to the film itself, the presentation has definitely dated aspects. What keeps the film in the category of a flawed classic rather than a dated curio is Frederick March's wonderful performance as Death who comes as Prince Sirki to a weekend gathering of Italian aristocrats at the villa of one of those aristocrats. March captures ideally the worldliness of an ageless figure, such as death, who has seen everything and his endearing naiveté as Death realizes he's actually experienced nothing of what he sees. It's when he falls in love with the beautiful Grazia that he begins to understand the suffering of which humans are capable. Indeed when Grazia wishes to go with Sirki/Death, Death feels the anguish that a person feels who must part from one he loves. It is when she declares that she knew who he really was all along and isn't afraid to follow him to his realm that Death grasps the power of love in the face of death. March conveys all of this beautifully and even makes his final rather overwrought speech memorable and moving.Unfortunately, from those thespian heights, the other aspects of the film are a rather mixed bag. The young actress who plays Grazia is given overdone dialog that irresistibly reminds me of the lines of the "serious" play that Katherine Hepburn's character in the movie, Backstage, is auditioning for. That's the play with the classic line, much parodied, "Father, the calla lillies are in bloom again..." Grazia's lines approach the laughable. Also, for a group of Italian aristocrats, the guests at the house sport frank American or English accents while the few working class Italians that appear are pure stage Italians out of the Chico Marx mold.But despite these limitations which led me to subtract three stars out of ten, it's a film well worth seeing.

View MoreThere is a subject that might be brought into the sphere of a masters degree thesis: how the destruction and death of World War I created a wave of theatrical and cinematic creativity dealing with life after death, and that death is not an ending but a beginning. This trend mirrored the rise of spiritualism (as pushed and advocated by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sir Oliver Lodge, and others) as a way of healing the real emotional losses felt by millions of people around the world after 1914 - 1918. It produced some works of stage and screen such as the anti-war FIFTY MILLION GHOSTS (attacking armaments king Basil Zaharoff - young Orson Welles appeared on stage in it), the play and film OUTWARD BOUND by Sutton Vane, and (probably best of all) Albert Casella's classic DEATH TAKES A HOLIDAY. It's still produced occasionally, and even made it to a television version (in 1971) and a recent remake (MEET JOE BLACK).Supposedly, as the "Lusitania" was going to the bottom of the Irish Sea, producer Charles Frohman said to his friends standing with him on deck, "Why fear death? It is the most beautiful adventure in life?" or words to that effect. Frohman (who did drown in the disaster) was quoting the words of his close friend and business associate James Barrie from PETER PAN. In a sense, Casella's story follows this particular point of view. Death (Fredric March) has come to the palazzo of Duke Lambert (Sir Guy Standing) and is intent on taking his daughter Grazia (Evelyn Venable), but instead makes a deal. He has heard a great deal about the human emotion of love, and has never experienced it. Instead, the only experience with human beings he has had was fear. So, he will not take any of Lambert's guests, family, or friends on this visit, if Lambert will allow him to stay as "Prince Sirki", a recently deceased nobleman whose form is available. Lambert agrees.The film actually (like the play) is quite probing, into the nature of death, love, and life itself. We see the various people who are in the palazzo, some of whom have lives of pleasure or adventure, and March constantly finds small flaws in these things that the humans overlook. When he meets one who races at high speed, he asks (straightforwardly, but with a heavy ironic undertone), "Why haven't we met before?" Henry Travers in a supporting role is a lover of fine food and drink - and obviously he too may soon meet March again under different circumstances.But it is Venable who is the key to March's humanization. She is not impressed by the wonders of life and the world her friends push. She seeks something more meaningful. A beautiful woman, she is pursued in the film (by Carrado - Kent Taylor), but finds his heavy sensual love not what she wants. It is only with March, also seeking an answer, that she finds the match to herself.March too is pursued, by the social climbing Gail Patrick and Helen Westley, and both are quickly shown the valuelessness of "titles" and status. March willingly shows them (briefly) his real self, and they flee him in terror. Both March and Veneble are incomplete: he by the seeming void in his eternal duty of ending life and being feared for it, she by her realizing what the book of ECCLESIASTES said two thousand years ago that is still true: "Vanity of Vanities...all is vanity!". The one exception is true love, and both find that in each other that goal is met. So at the end Grazia willingly goes with Sirki, because there is no fear for both when together - for together they can face the universe and eternity.

View More