Purely Joyful Movie!

Brilliant and touching

A lot of perfectly good film show their cards early, establish a unique premise and let the audience explore a topic at a leisurely pace, without much in terms of surprise. this film is not one of those films.

View MoreStory: It's very simple but honestly that is fine.

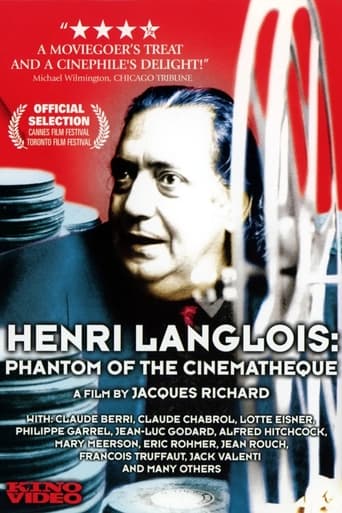

Until I watched this documentary on TCM, I did not know or heard of Henri Langlois and was amazed to learn what he did for cinema. He went through great trouble and hardship to be able to collect and preserve these movies and memorabilia. Watching his interviews and footage you can appreciate his love for cinema and the best part of him was that he collected movies from all over the world unlike some others who only preserved what they liked. Great directors owe their success to this man as he made it possible for the younger generation to have a chance to watch great works of cinema in his theater. One can appreciate his efforts knowing when he started to show these movies, VHS and DVD's were not available and if you missed a movie once it was on big screen, you may never get a chance to watch it. Watching this documentary, I realize that my collection of DVD's would have not been as large if it wasn't for Mr. Langlois. Henri Langlois was a visionary and ahead of his time by decades. Too bad not too many people know about him.

View MoreSadly, over the years most of our older films have been lost-- intentionally destroyed or simply disintegrated since they were made using highly unstable nitrate stock. I've heard estimates that between 50-80% of the films pre-1950 have been lost--mostly because no one had the will to save them. In this climate of ambivalence, Henri Langlois is unique in that as far back as the 1930s, he was, on his own, working feverishly to save what he could of these precious pieces of our history. This documentary both chronicles his efforts as well as points out the impact he had on the film industry--as well as the total ambivalence or outright hostility he encountered from his own government.What was most fascinating about Langois is how for him saving cinema history was not just a passion but an obsession. He didn't particularly care about his clothes or hair or even saving money--every ounce of his energy was spent on film preservation as well as spreading his love of cinema. Throughout a 40 year period, he and the fledgling organization he built operated on a shoestring budget--spending every penny on buying and conserving every film he could possibly obtain. How he managed to beg, borrow, steal (in some cases) and cajole people into parting with these films is fascinating and proved that for Langois it was his all-consuming passion.As a result of his efforts, he was able to introduce classic cinema to audiences in the 1950s and 60s and this had a huge impact on inspiring the French New Wave film movement. Interviews with Truffaut, Godard, Romer and others all point to Langlois as sort of a "Pied Piper" who led them to want to create their own films. Later, this impact spread abroad--eventually leading to Langlois receiving a special Oscar for his contributions to film.Now had this only been the thrust of the documentary, it would have been well worth watching. HOWEVER, the story has a much darker side. Despite all of Langlois' efforts, once he gained some prestige and public attention, he seemed to have constant battles with the French government and small-minded people who wanted to wrest control of Langlois' "Cinématheque Française"--a repository and eventual museum dedicated to film preservation and worship. A few of these people actually were interviewed for the documentary, though unfortunately there were only a few clips of these tiny-brained idiots--I really would have liked to hear more about how they could justify taking an organization like Cinématheque Française and destroying or severely limiting it. While it was obvious to practically everyone that almost all the conserved films would have been lost without Langlois AND it was also obvious Langlois was spending every dime acquiring as many films as possible, people (mostly in the government) were critical and even tried to remove him from the very foundation he created! I think the motivation of many of these individuals was "if I can't have a piece of this, then I'd rather destroy it".Fortunately, the New Wave artists and the world rose up as a result of an attempt to replace Langlois with a political hack (nicknamed "the Langlois Affair"). And, following this huge showdown, Langlois was able to finally build a large and worthy film museum. He was so dedicated to this, that according to this documentary, he would fall asleep in the half-built site--only to awaken a couple hours later and continue his manic efforts.So, once the museum opened in the 1970s, this was the end of Langlois' struggle? Well, unfortunately no. Only a decade later (after Langlois' death), critics began complaining that the museum was stale and needed to be either updated or completely redone in a NEW building--even though the museum was only a decade old. And, when there was a minor fire at the museum in the 1990s, the powers that be decided to put most of the museum in moth balls for over a decade--allowing only a tiny fraction of the holdings to be seen at any time! Langlois must have been rolling in his grave like a rotisserie, though the story is not completely sad. Though the original museum is no more, there is a new museum (finally) and more importantly Langlois' enthusiasm for preservation spread like wildfire--leading to dozens of other film repositories across the globe. For example, in the 1940s and 50s, there were NONE in the United States but today there are about a dozen archives--saving everything from the early silents to documentaries to classic Hollywood to international films.This documentary is an absolute must-see for anyone who considers themselves a "Cinephile"--a lover of film. I am not talking about people who go to the theater weekly, but people who adore film--the history, the preservation and almost the worship of film. If you fall in that category, then it's imperative you see this movie--especially since the creators of this documentary used decades of film to piece together this project. Clips of Langlois from the 40s and 50s all the way up to his death as well as recent clips were all used to create a fascinating montage that is sure to inspire.Thank God for men like Langlois.

View MoreI had the chance to check out this fantastic documentary some time back at one of our local art cinemas (unfortunately the U.S. cut). After films about films (Day For Night, anyone?), I love documentaries about films. Make no mistake about it, this is a cinematic love letter to one of French cinema's patron saints. The film features scads of interviews with those who knew & loved (or hated) Langlois. As I watched it, I tried to imagine what it must have been liked to have attended a film at the Cinematic Francais,back in the day (with the likes of Truffaut,Goddard & Rivette sitting just inches away from you). This is a film that any/all serious film fanatics should be going out of their way to see. Perhaps one of these days, we may even get to see the 210 minute French cut of the film one of these days.

View More...Because, as this documentary makes quite clear, Langlois was one of the greatest film geeks that ever lived, and it would be heaven-sent (if there is a heaven) to have him back at the Cinematheque again. And I say the word 'geek' with the utmost enthusiasm and admiration and respect et all. Langlois was not just a film buff's film buff (no New-Wave without him, hence probably most of today's cinema), but also open to anyone who might be interested in checking out his museum of cinematic wonders, where he collected objects and put them in the spaces and hallways with brilliant ease. He was probably the greatest programmer of any privately functioning theater ever. After amassing 50,000+ film prints over a span of a couple of decades, the Cinematheque in Paris became THE place where fans of film (and auteurs to be exact) could come and see entire careers of a director, or, more importantly, even bring their own film or a 'heisted' print to be included in the archives. It was no surprise then when an incredible uprising occurred over Langois being ousted in 1968, and when finally re-instated things could never totally be the same again.Rarely have I seen someone documented who in a way is as important to the history of film as any other important filmmaker from any part of the country. As Jean-Luc Godard says at the start of the film, "Langlois was like a film producer who produced a way of seeing films." He was in large part preservationist who held onto original negatives (sometimes in nitrate form) and re-cut the films when only scraps and fragments remained of masterpieces, leading to people being able to see many films that would otherwise be lost. He was also in large part as enthusiastic as a little kid with a new toy when it came to finding an old silent film from Murnau or Eisenstein or something from Jean Vigo and sharing his love with other people who would either go on to be filmmakers themselves (the 'New-Wave', to be sure, but also film historians), or the casual amirer of films. And another part was the museum he had built up like any other art museum, with the finest pieces of wares and artifacts (i.e. the original 'mother' head from Psycho), to invite film fans and even casual viewers to gorge on more than just memorabilia.It then becomes bittersweet - at first sweet- to see his story unfold via many interviews with associates, friends, filmmakers (Chabrol, Roche, etc), and historians who knew how Langlois started small with passionate screenings in the 30s, then into a sort of resistance fighter for his films from the Nazis in the early 40s, and then finally expanding in the late 40s into the 50s to become the premier place for films that, unlike any other archive, were all inclusive for the audience. So, in a sense, we learn he was a filmmaker, but really as one who could make the films important and vital and presentable. He wasn't alone, as we learn throughout this entertaining look at his ups and downs of his career- we also see a bit into his personal life with his most close associate and love Mary, who was like a mother with tough love attached at times. Then, eventually, we see how he also had enemies, maybe as many as he had friends and followers, and somehow (he wasn't "executive" material of course, and because he was private and with next to no funding from the French government, near dirt-poor while scrapping everything for his non-profit organization) he got fired. It's amazing- on top of the previous footage of various film clips from the films he showed &/or directors inspired (Vigo, Godard, Meilies, Von Strernberg, Murnau, etc)- to see the revolution-style protests of his being fired by film directors and fans. It's actually, in all manner of speaking, inspiring.But then the bitter part comes in seeing what Langlois was reduced to after being reinstated- taking professor jobs on cinema across America and Canada and France- just to get a little more money for the fledgling Cinematheque. All of this ends up being told through Langlois and the other interviews as something that is saddening, but there's still always hope and more films to be shown all the while. While towards the end director Jacques Richard has the film lagging in the section about Langlois and his work on the museum, overall he really delves deep into this wonderful man's life, and provides a great way in documentary form to introduce future film-buffs into what it means to really put yourself completely on the line for film. On top of this, what it means to be independent of the system and get your stuff shown through someone who wont brush someone off with a desire to display their art (the film the Dreamers put a good memory on the Cinematheque right at the start, though only briefly). Someone like Langlois, who was scruffy and boisterous and extremely intelligent and acute on anything film and preservation-related, also was great in how he wanted to look to the future just as much as looking to the past. Like any other print at the Cinematheque, this documentary deserves to be preserved too.

View More