Brilliant and touching

A brilliant film that helped define a genre

Not sure how, but this is easily one of the best movies all summer. Multiple levels of funny, never takes itself seriously, super colorful, and creative.

View MoreBlistering performances.

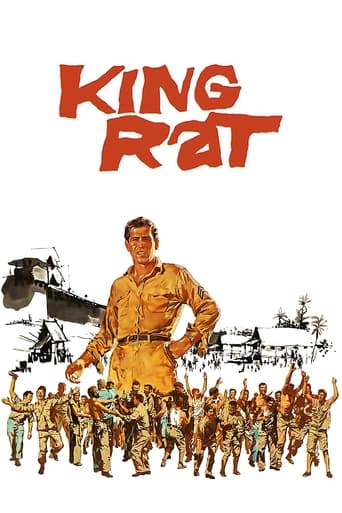

This WWII prison camp drama set in the steaming Burmese jungle is a metaphor for the horrors of World War II and features what is easily George Segal's best dramatic performance, an even better one by James Fox, and lean, taut direction from Bryan Forbes. It also offers many insights on the British class system and takes a very grimly pessimistic view of the human condition. There is some humor but it is darkly sardonic and somewhat sadistic in nature. Segal's con artist extrodinaire Sergeant King is the dark side of Segeant Bilko and he employs bitter cynicism as opposed to the wisecracking humor of Phil Silvers. It is based on a novel by James Clavell, and is a better film, if not more entertaining, than the author's "The Great Escape," which was released a couple of years prior to "Rat." With the exception of Segal, the British cast members greatly outshine their American counterparts. Tom Courtenay, the always wonderful Denholm Elliott, John Mills, Gerald Sim, Leonard Rossiter, and Alan Webb all contribute memorable characterizations, but by far the best is James Donald as the compassionate, humane camp doctor, practically reprising his role of eight years earlier in "Bridge on the Rver Kwai' also set in a Burmese prison camp.

View MoreLawrence Kohlberg wrote a controversial and much discussed paper about the stages of moral development at the U. of Chicago in 1958. Kohlberg asserted that moral development ranged from conditioned obedience and fear of punishment through self-interest, conformity, authority for the sake of maintenance of social order, and consciously made social contracts, to awareness of universal ethical principles. While still subject to argument, a number of psychometric tests have been adapted or specifically developed to test the accuracy of Kohlberg's notions. To this day, his ideas strongly influence measures of anti-social, sociopathic and sadomasochistic thought and behavior in criminal justice and other endeavors. Take a look at it on, say, Wikipedia, and then watch "King Rat" closely to see where the various major characters fall on the scale. Further, one can utilize "KR" as an illustration of socialized, acculturated, "normalized," and belief-bound -- vs. chillingly empirical, anti-socialized, anti-ac-CULT-urated, ab-normalized, observation-driven -- appraisal of events. The former may well be "just" and "fair," but relatively ineffective when it comes down to survival... and the latter may be "ruthless" and "vicious," but relatively effective therefor. "KR" demands one climb out of the box of "delivered truth" based on authoritarian in-struct-ion to "get it." In modern neuropsychological parlance (see, for example, Iain McGilchrist), it requires that one pretty much abandon the rules and regulations of the brain's verbal- symbolic-skewed left hemisphere for the open-mindedness of spatial- sensory-skewed right. Even though the 1950s had been a watershed decade for existentialism and the 1960s a decade of wider distribution therefor, "King Rat" was =far= ahead of its time in the English-speaking world. But if one could have seen it in the Russian-speaking one (not possible during the Cold War, after all), anyone who'd read Dostoyevsky and Chekov -- let alone lived in a gulag -- would have sussed it immediately. RG, Psy.D., "The 12 StEPs of Experiential Processing," online.

View MoreIMHO most of James Clavells novels are pretty humdrum affairs but 'King Rat' really hits the top notch. To me it is one of the 20th centuries GREAT pieces of literature in Clavells masterful exploration of how various members of a society manage to live on the edge of survival.However, to attempt to portray this in a feature film is like watching a formation air display on a pocket TV screen, or enjoying a steak by liquidising & sucking it up through a straw. It has no hope of doing the subject matter justice.I can see so much valuable material left out and so many shortcuts that it can only fail. However, I realise that a feature film is a medium that reaches vastly more people than any other and this was a very good attempt. Very well cast, well acted and well directed.Perhaps a mini-series? 'King Rat' is well overdue for a remake of some sort.

View MoreNo need to repeat the plot. As I recall, the movie got good reviews at the time, sending me quickly down to the local theatre. However, the downbeat story and dour b&w setting have likely limited the appeal over the years. Then too, director Forbes films in a leisurely impersonal style using a script crowded with sometimes hard-to-follow characters. That being said, this is still a fascinating film for both characters and ideas.So, is Segal's resourceful corporal an admirable character or not. To me that's a central question posed by the movie. Segal's corporal is a born deal-maker and realist who sees opportunities where others, more rule-bound, do not. As a pow, he's a born survivor. He not only succeeds in the camp, he flourishes, using his sly leadership abilities to set up what amounts to an illegal combine with paid pow employees. In short, he's a natural entrepreneur, and those reviewers who see him as embodying the spirit of American capitalism have a definite point. However, I think the screenplay fudges by implying that he's something of a failure on the outside. Strikes me that his ability to take stock of a situation and respond intelligently, if selfishly, would make him a success even under normal social conditions. In this restricted sense, I see him as rather admirable. After all, "buccaneer" capitalists are often admired in real life. But, I also see the circumstances in the movie as not being that simple.Segal's opposite is Tom Courtenay's provost marshal (camp law-enforcer), who's also the ultimate bureaucrat. Rules mean everything to him. The fact that Segal keeps bending and breaking the rules poses not only a professional threat to Courtenay, but a personal one, as well. Note, for example, how shattered he is when finding out that camp corruption (breaking the rules for personal gain) extends beyond Segal to even the commanding colonel (Mills) himself. It's really Courtenay, not Segal's pal, the compromised Marlowe (Fox), who's the movie's genuine idealist. In true idealistic fashion, Courtenay carries over established rules and authority from normal contexts, expecting them to produce the same results even in this more extreme context. But camp conditions have produced what amounts to an altered military context—it's now a subtly Darwinian context in which the rules work against talented realists, like Segal, who instead use them to advance their own survival. Segal understands this, while Courtenay does not, at least not until that shattering moment when the colonel extends the corrupting offer of a captaincy to him. Thus, the role of rules in regulating how prisoners are supposed to behave becomes a factor in assessing whether Segal's conniving corporal is admirable or not. The significance of the camp rules is easily overlooked because they're associated with either the Japanese captors or the rather priggish, dislikable Courtenay or even the corrupt colonel, none of whom possesses the sly charm of the roguish Segal (in an excellent performance). However, collectively, the rules can be justified by arguing that without them, the camp would collapse into anarchy in which likely no one would survive. Now, however that may be, there's one rule paramount in the screenplay. And that's the rule covering the equitable apportioning of food. Scales and weights are used to insure that outcome. The purpose presumably is to give each man an equal chance at survival. It's a principle of fairness in action. Note the strong reactions when there's suspicion of tampering and the "bore hole" that awaits transgressors. To me, this is a crucial point in judging Segal's character, but one that is not, I believe, made clear by the screenplay. We do know that the tampering is condoned by at least some of the higher-ups, but crucially we don't know (though I may have missed something) whether Segal is in on the tampering. Now, to this point, Segal's transgressions appear relatively benign— making shady deals that seemingly do no lasting damage. However, if he's in on the tampering, then he is doing lasting damage to the men whose rations are being shorted. He's betraying them in a tangible way. As a result, conventional morality (justice as fairness) would certainly condemn his action and find him not in the least admirable. If I'm correct about the screenplay being unclear about his involvement, then that might have been the writer's intention so that we leave the movie with appropriately ambivalent feelings about its central character. Anyway, to me, the question of Segal's character turns on whether he's just a shady and resourceful entrepreneur or whether he's a ruthless and calculating criminal ("criminal"in a larger sense). Either way, however, the movie remains chock-full of interesting ideas and is well worth catching up with.(In passing—there's a curious irony that's so far passed unnoticed in the reviews. Note how forcefully Fox's disillusioned Marlowe denounces the padre's religious belief. How, Marlowe wonders, can the padre's conventional god allow such grievous calamities as the camp to exist. In fact, that's a logical challenge to standard theology. This god, Marlowe continues, must be either feckless or wicked. In fact, he asks, what can this ineffectual god do? Seemingly unruffled, the padre answers succinctly— He can heal. Understandably, amidst all the camp suffering, Marlowe scoffs at the unexplained response. But later, there's Marlowe's crushed arm and Segal's timely {though mercenary} intervention with healing anti-toxins. Viewers don't have to agree with the theology in order to appreciate the subtlety of a script that leaves it up to the viewer to make the connection.)

View More