People are voting emotionally.

I think this is a new genre that they're all sort of working their way through it and haven't got all the kinks worked out yet but it's a genre that works for me.

View MoreThe film's masterful storytelling did its job. The message was clear. No need to overdo.

View MoreStory: It's very simple but honestly that is fine.

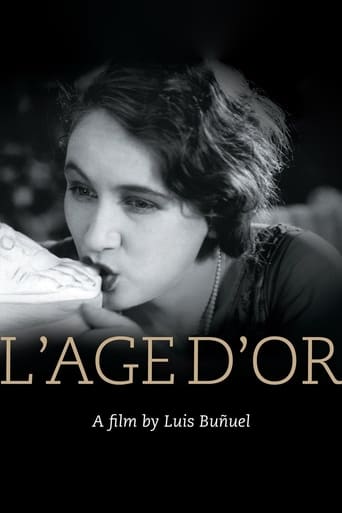

Surrealism and sour attack upon religion by the Spanish master , the great Luis Buñuel .This is a typical Buñuel film , as there are a lot of symbolism and surrealism , including mockery or wholesale review upon religion, especially Catholicism . This film opens with a documentary on scorpions (this was an actual film made in 1912 which Luis Buñuel added commentary) ; later on , a man (Gaston Modot) and a woman (Lyla Lys) are passionately in love with one another, but their attempts to consummate that passion are constantly interrupted by their families, the Church and bourgeois society.This is a strange and surrealist tale of a couple who are passionately in love , but their attempts to consummate it are constantly thwarted ; it is an absurd , abstract picture that was banned for over 50 years. This is the most scandalous of all Buñuel's pictures . It is packed with surreal moments , criticism , absurd situations and religious elements about Catholic Church ; furthermore Buñuel satirizes and he carries out outright attacks to religious lifestyle and Christian liturgy . Luis Buñuel was given a strict Jesuit education which sowed the seeds of his obsession with both subversive behavior and religion , issues well shown in ¨Age of Gold¨. Here Buñuel makes an implacable attack to the Catholic church , theme that would preoccupy Buñuel for the rest of his career . It is surreal , dreamlike , and deliberately pornographically blasphemous . Buñuel made his first film , a 17-minute longtime short film titled "Un Chien Andalou" (1929), and immediately catapulted himself into film history thanks to its disturbing images and surrealist plot , the following year , sponsored by wealthy art patrons, he made his first picture , this scabrous witty and violent "Age of Gold" (1930), which mercilessly attacked the church and the middle classes . Buñuel's first picture has more of a script than ¨Un Chien Andalou¨ , but it's still a pure Surrealist flick . For various legal reasons, this film was withdrawn from circulation in 1934 by the producers who had financed the film and the US premiere was on 1 November 1979 . This film was granted a screening permit after being presented to the Board of Censors as the dream of a madman . However , on the evening of 3 December 1930, the fascist League of Patriots and other groups began to throw purple ink at the screen, then rushed out into the lobby of the theater, slashing paintings by Yves Tanguy, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, and Man Ray . This is an avant-garde collaboration with fellow surrealist Salvador Dali in which Buñuel explores his characteristic themes of lust , social criticism , cruelty, anti-religion , bizarre content , hypocrisy and corruption . This is an ordinary Buñuel film , here there are symbolism , surrealism , being prohibited on the grounds of blasphemy .The motion picture was compellingly directed by Luis Buñuel who was voted the 14th Greatest Director of all time . This Buñuel's strange film belongs to his first French period ; he subsequently emigrated to Mexico and back to France where filmed other excellent movies . After moving to Paris , at the beginning Buñuel did a variety of film-related odd jobs , including working as an assistant to director Jean Epstein . With financial help from his mother and creative assistance from Dalí, he made his first film , this 17-minute "Un Chien Andalou" (1929), and subsequently ¨Age of Gold¨ . His career, though, seemed almost over by the mid-1930s, as he found work increasingly hard to come by and after the Spanish Civil War , where he made ¨Las Hurdes¨ , as Luis emigrated to the US where he worked for the Museum of Modern Art and as a film dubber for Warner Bros . He subsequently went on his Mexican period he teamed up with producer Óscar Dancigers and after a couple of unmemorable efforts shot back to international attention , reappearing at Cannes with ¨Los Olvidados¨ in 1951 , a lacerating study of Mexican street urchins , winning him the Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival. But despite this new-found acclaim, Buñuel spent much of the next decade working on a variety of ultra-low-budget films, few of which made much impact outside Spanish-speaking countries , though many of them are well worth seeking out . As he went on filming "The Great Madcap" , ¨The brute¨, "Wuthering Heights", ¨El¨ , ¨Susana¨ , "The Criminal Life of Archibaldo De la Cruz" , ¨Robinson Crusoe¨ , ¨Death in the garden¨ and many others . His mostly little-known Mexican films , rough-hewn , low-budget melodramas for the most part , are always thought-provoking and interesting ; being ordinary screenwriter Julio Alejandro and Luis Alcoriza . He continued working there until re-establishing himself in Europe in the 1960s as one of the great directors . And finally his French-Spanish period in collaboration with producer Serge Silberman and writer Jean-Claude Carrière with notorious as well as polemic films such as ¨Viridiana¨ ¨Tristana¨ , ¨The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie" , of course , ¨ ¨Belle Du Jour¨ , with all the kinky French sex and his last picture , "That Obscure Object of Desire" .

View More"L'Age D'Or" carries one simple, yet extremely frustrating paradox, if we use our intelligence to extract from the images' symbolism some depth and substance, we're among the privileged ones, those who 'got' the film, who understand it's powerful diatribe against religion, bourgeoisie, patriotism, an ode to freedom, anarchy, whatever ... but if the same process generates a more critical opinion, we are reminded that it's a surrealist film and that we shouldn't pay too much attention to the 'story' but rather focus on its dream-like escapist value..Now, I'm puzzled, if the film has a point to make - I believe it has- then it should encourage some criticism that wouldn't deny the gutsy approach of Bunuel and Dali and the political significance of their second feature. Speaking of the first, I loved "Un Chien Andalou" for what it was, a brilliant piece of surrealist film-making, granted the images had no connection whatsoever, each one was powerfully defying all our preconceived ideas about what Cinema should stand for. "Un Chien Andalou" was the standby of concept, the exhilaration of Cinema as a rule-less art-form relying on the basic premise of hypnotic images, pleasing or shocking to the eyes, but ultimately fascinating, Cinema, like music and dancing, a hymn for human's quest for liberty and new forms of expressions.Yet there's a major difference between "Un Chien Andalou" and "L'Age d'Or": length. "Un Chien Andalou" has a dream-format, it's short but rich, and even if the original intent was that ""No idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted.", the film allowed us to transcend our capabilities to judge a film on a rational basis, and discover the inner poetry and craftsmanship of Bunuel as director and storyteller, which is even less surprising when you know that he was influenced by a poet named Garcia Lorca, and a painter (man of images) named Dali. "Un Chien Andalou" is the kind of 'experiences' that gets richer and subtler after each viewing, and in its own way, it's an enjoyable film, if not 'entertaining'.The irony is that the film was intended to shock, to be a cinematic slap addressed to all the establishment, but actually met with a fair success. Both Bunuel and Dali didn't expect such recognition and probably thought they missed their point, since even the upper-class audience applauded the film, why couldn't they, after all, embrace its dream-like poetry? Aren't people with more free time in their hands the most likely to enjoy the artistic freedom superbly displayed? As a result, I believe Bunuel and Dali wanted to make a film with much more explicit anti-establishment messages, with the closest structure to a plot. I respect that new approach, but with this mindset, it's difficult to sit through the whole hour without noticing some "perplexing random bits of creativity".I'm not judging them negatively, but 'random' seems to me the right word, while it was fitting for "Un Chien Andalou", "L'Age d'Or" featured many moments that seemed totally out-of-place even from surrealistic standards : a cow in a bed, a blind man violently kicked, a documentary sequence about scorpions, not to mention the ending's Biblical undertones I'm aware that these parts carry some symbolism and are not gratuitous, but then again, who had to read 'Wikipedia' to understand what the film was about? Who had to make some researches before jumping to the conclusion that even the craziest stuff made sense? The film only works when you know exactly what was its first intent whereas for "Un Chien Andalou", only being familiar with the notion of surrealism was enough, and even then! I guess what I'm trying to say is that the intent of "L'Age d'Or" is laudable and the film is never more powerful as when it doesn't try to be a second opus of "Un Chien d'Andalou", the whole film starting with the Majorcans until the party, would have been better, but it's just as if Dali and Bunuel wanted to shock for the sake of it, and used 'surrealism' for their slap-in-the-face moments, while it was more than symbolism, than open for interpretations, therefore criticism. I remember I said about "Ingmar Bergman's "Persona" that the film "rises above rationality with such beauty and self-confidence that if there ever was one word intelligible enough to translate the power of its images, the film would have failed." The same sentence could have applied for "Un Chien Andalou", but "L'Age d'Or" is not a disinterested film, it's not art for art, it's art with a point and the criticism only consists to question whether the film succeeds to make its point, or not.Why the scorpions? Why that ending? Why oh why, did they make the actors talk, since the delivery was so laconic and obvious bad acting? Why not keeping the film silent, relying on its powerful message? I have the feeling that by trying to make a political pamphlet in one side, and remain faithful to their surrealistic agenda, the two effects canceled each another and the political core of the film is undermined by these random bits of absurdity. Maybe this is why I can't truly enjoy "L'Age d'Or", not as much as "Un Chien d'Andalou" anyway. This is why I couldn't wait for the film to end I started my discovery of Bunuel from his later works "The Discreet Charm of Bourgeoisie", "This Obscure Object of Desire" and "The Diary of a Maid" so I'm aware that being a man of creative genius isn't incompatible with making movies with relative consistence or let's say, coherence."L'Age d'Or" might be victim of its own ambitions, but shouldn't be above criticism just because it's a surrealistic film; otherwise, it shouldn't even be applauded for its intelligent subversion. I think it's fair to say that it's an important film, powerful, historically and culturally significant but certainly not flawless.

View MoreIn order to understand this film one should know something about the history first.One should be aware of the miseries inflicted by man on another man due to reasons which I dare not mention here. It is not just cinema it is a STATEMENT,& GREAT BUNUEL was one of the very few who could make it. No other director in the profound history of cinema can ever touch a subject in this intricate yet absurd way.well, surrealism is often included in most of his films but i think the way he portrayed it has no parallel.I mean ,Bunuel never cared about awards or anything ,as to me the whole community of people who organize or are in the jury of any prestigious awards never meant much to him. He did what he always wanted to &that makes him to me as Hitchcock aptly said THE GREATEST FILMMAKER OF ALL TIME.

View MoreL'Age D'Or is pure cinema, as silent films were, and despite how difficult it may be to feel absorbed in it, it really is a great work. It consists of a series of tightly interlinked vignettes, the most prolonged of which tells the goofy satirical story of a man and a woman who are keenly in love. Their efforts to have sex are always obstructed by their families, by the Church and the bourgeoisie. In one attention-grabbing moment in the film, the woman passionately sucks on the toe of a religious statue as if it were a phallus, the iconoclasm of which is remarkable considering the time at which this movie was made, and consequently banned.Salvador Dali, the hugely amusing surrealist painter, co-directed this film with Luis Bunuel, and the tone of many of his paintings is captured in many moments of the film but in the appropriate manner for its medium, such as the scalps of the women flapping in the wind on a crucifix accompanied by cheerful music, or the twisted black humor of the final vignette, which uses comic-strip-like symbolism and details to tell of a Marquis de Sade-style orgy, the survivors (!) of which emerge, one of them reminiscent of the most conventional image of Jesus.Upon viewing, I was muddled by all of this. I laughed a bit, my eyebrows curled, and I didn't quite understand, perhaps because I'm not accustomed to the proper manner in which one views a a silent film from 1929, but I did reflect upon it and it grew on me, because I do believe that if this film were not banned by the ever-predictable church and the governments they still influence, it would have moved the viewers of its era to open its eyes a bit more to sexual repression, whether propagated by civil bourgeois society or by the church, and ponder the film's most plausible implication, which is that repression generates violence, which is very true. The fiendish gag is in the look of dog-tired depravity as Christ emerges like a De Mille figure staggering of De Sade's party.

View More