A Disappointing Continuation

I wanted to like it more than I actually did... But much of the humor totally escaped me and I walked out only mildly impressed.

View MoreIf you're interested in the topic at hand, you should just watch it and judge yourself because the reviews have gone very biased by people that didn't even watch it and just hate (or love) the creator. I liked it, it was well written, narrated, and directed and it was about a topic that interests me.

View MoreThe movie really just wants to entertain people.

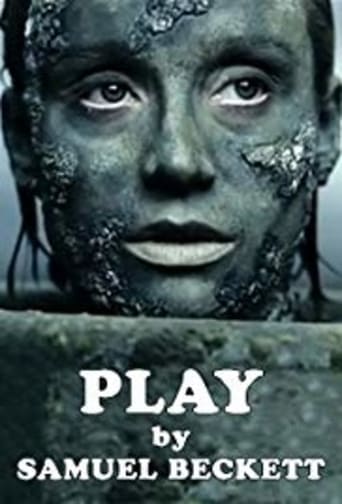

This is a filmed play; one must judge it as such. Minghella's rapid reaction camera takes the place of stage direction for a spotlight. But that's about it. The full 16 minutes (8 mins of script with the instruction to repeat) are played out with little intervention from the director, save cutting or inter-focusing between the three talking heads and mixing head-shot with super-closeup.The three characters live out a collapsing love-triangle. Is it happening now? Are they living over what has already happened? Is this a dramatised overview of what always happens? These are all valid questions as the script is delivered, overlapping, at barely digestible speed. Juliet Stevenson (the mistress) is the most interesting, allowed a full expressive range throughout her role, including a flash-dispatched orgasm. Most hilarious is Rickman's man-at-the-centre (literally as well) who retreats into talk of tea when he's not got the hiccups - an important element, this impediment, as it has the same worth of content given the monotone delivery. Kristin Scott-Thomas' trademark 'disinterest' makes up the trio.I like Minghella's top-n-tail affectation of the rushes cards, which brings into relief the 'play' suggestion of the title. Is this a record of the consequential comeuppance coming for the characters? Or is it simply as valid a circumstance as the next for working out the old rite of cheating relations? 6/10

View MoreAnthony Minghella follows much of Beckett's stage directions with his filming of "Play", but he also takes some pandering liberties that hurt the internal logic of the piece. In a stage production, we would see three characters in urns: from left to right, W1, the wife; M, the husband & lover; W2, the mistress. (This, by the way, was not Beckett's published arrangement, but one he chose when he directed "Play" some years later.) They are in urns, and we can see only their faces, covered with some of the same material as the urns. They speak only when a light, shone from below, is upon them, and the light flits from face to face, fragmenting each monologue, so that we slowly pick up the thread of the love triangle & that each of them is now in some afterlife, not knowing that the other two are beside. They speak rapidly and in a monotone, and the entire play is repeated.Minghella changes the light to a camera. He places these urns in a larger field of many urns, each babbling its own story, and he gives the feeling of old film, with the sounds of film rattling in the projector in the start & snapped off at the end. These are intelligent means of adapting the play to a film. He, however, cannot keep the camera still, so that we see the characters from the side, not merely from the front. This lessens the intensity & the logic of the questioning coming from a single point. Part of what makes "Play" effective theater is the strong sense of confinement. This is more difficult in a film, and even more difficult on video, but it loses even more of that sense when the camera cuts from one angle to another.The play is well-cast & well-acted. The actors keep to the rapid-fire rhythm & the flat voices. Minghella's rhythm gives nothing to an audience. We must pick it up on the fly, very quickly. If he could only have kept the camera still, close up, face front, then it would've been perfect.

View MoreAlmost impossible to understand for a non-native speaker (I bet even native speakers would have difficulties). But worth seeing. Thrilling, in some way. I didn´t understand much of the story (if it has one) and would need to see it again and again, but it is impossible to get it in Germany (lucky I´ve seen it at all!). It´s a shame, because "Play" is just fascinating.

View More'Play' is one of Beckett's most delightful confections, a farce, a vision of hell, a discordant fugue, a logorrheic din: as much a parody of Sartre's 'Huis Clos' as Sunday supplement suburban entanglements.Three heads - a man, wife, and mistress - look out from urns, and relate the story of the man's affair and the wife's reaction to it, in a rhythmic, overlapping gabble, repeated twice to convey the idea of eternity. These lives, brought to crisis point by a very physical interruption - adultery -are condemned to a disembodied, inhuman, mechanical repetition of a previous existence.Here, Beckett's interest in memory is at its most alienated - recalling the past is not an act of retrieval, an attempt to piece fragments of a shattered identity as in, for example 'Krapp's Last Tape'. It is a punishment, devoid of poetry, oppressively banal. Worse, the reminiscences are prompted by an unseen lighting man, like a Gestapo interrogator, switching speedily between characters, creating the play's rhythm, forcing them into 'life'. Much as they might like to, they cannot hide, they are at this man's mercy.You can imagine the effect in the theatre: not only is the mundanity of everyday life shown to be mechanical, barren, dead, with the urns and the repetition not a metaphor for hell or limbo, but for life; but the way these insignificant lives are interrogated, as by the Gestapo, or God, or their own conscience, or paralysed desires, or us, or SOMEBODY, forces us to admit that we don't live very well.Minghella, unlike his 'Beckett on film' collaborators, eschews over-fidelity. He keeps Beckett's words, but is radically unfaithful (a compliment!) to the play, liberated from theatrical constraints. His bombardment of montage; his intrusive use of colour, sound, camera angles; his turning Beckett's lighting man into the camera, with its clicks and whirrs and zooms; all fundamentally destroy Beckett's theatrical space.A condition where hell mirrors suburban life, where immobility , darkness, emptiness, inertia are the tenets, is given an incongruous energy, a visual excitement. Beckett's verbal and lighting rhythms are transformed into those of editing. Life in hell no longer seems that dull and repetitive; neither, by extension, do our own lives. The intrusive, oppressive interrogation of the light becomes the more distanced voyeurism of the camera - it is not this latter that breaks the space but the editing.This is an excellent example of an artist freeing himself from constraints, undermining his text, while remaining superficially faithful. Surely the appropriate response to 'Play' is to play. A very brave adaptation.

View More