Really Surprised!

A Brilliant Conflict

It's the kind of movie you'll want to see a second time with someone who hasn't seen it yet, to remember what it was like to watch it for the first time.

View MoreThe movie turns out to be a little better than the average. Starting from a romantic formula often seen in the cinema, it ends in the most predictable (and somewhat bland) way.

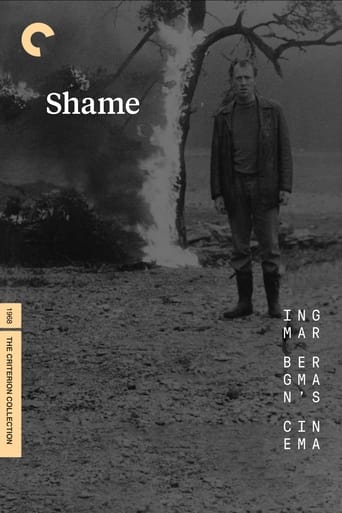

View MoreIngmar Bergman's psychological study of how humans react in a situation of war. The film takes place on Gotland, where invasion forces arrive.Pauline Kael reviewed the film in December 1968, writing, "Shame is a masterpiece, – a vision of the effect of war on two people, – but – it has many characters and incidents – in many ways, (it is) Bergman's equivalent of Godard's Week End – also an account of what people do to survive – Liv Ullmann is superb in the demanding central role, – Gunnar Björnstrand is beautifully restrained as an aging man clinging to the wreckage of his life. The subject is our responses to death, but a work of art is a true sign of life." Bergman is always great, at least in the black and white era. I'm less a fan of his color films. But when you have that crisp, bleak back and white cinematography and Max von Sydow, you can do no wrong.

View MoreI have found many of the films of director Ingmar Bergman (The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, Persona, Cries and Whispers, Fanny and Alexander) in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, and this was another Swedish film featured in it that I watched. Basically a civil war is occurring, and musicians and married couple Jan Rosenberg (Max Von Sydow) and wife Eva (Liv Ullmann) escape the devastation in society to a rural island and farm, there they remain indifferent to politics, they will communicate with only a few people, and the only luxury they have is wine. Jan and Eva love each other, but problems develop when Jan becomes upset with the war, weeping and becoming sensitive, and Eva wants to have children, but he does not, and they cannot escape the warfare as rebels attack and their neighbours are killed. Order is restored on the other side of the fight, but the couple are arrested for enemy collaboration, but following the fright and abuse against them they are released by local Colonel Jacobi (Gunnar Björnstrand), and he becomes a frequent visitor at the farm, but it is not clear whether he is just being friendly or trying to pursue Eva, at one point she gets money from him. Chaos ensues with the return of the rebels, at one point Jan is given a gun by the soldiers and told to kill the Colonel, he does so, and over the period of time becomes increasingly violent and murderous, until eventually the rebels flee, but the question remains as to whether Jan and Eva can truly escape the war, and if they can what happens next? Also starring Sigge Fürst as Filip, Birgitta Valberg as Mrs Jacobi, Hans Alfredson as Fredrik Lobelius, Ingvar Kjellson as Oswald and Raymond Lundberg as Jacobi's son. Apparently this film is part of a trilogy, the second instalment following Hour of the Wolf, Von Sydow is good acting selfish, immature, treacherous and cowardly, Ullman is good being strong and tender, together they make an intriguing pair of concert violinists and married couple. I will confess that I found the film slow at times, the most interesting moments came from the warfare material, and these moments do feel nightmarish and chilling as it interferes and diminishes love, beauty and trust, I don't fully agree with the four stars out of five by critics, but I know it is not a bad drama. It was nominated the Golden Globe for Best Foreign-Language Foreign Film. Worth watching!

View MoreWithout question, Bergman was a master when it came to the cinema of alienation; presenting characters with a singular point of view that is at odds with the world around them, leaving them inevitably cut off and isolated with their own distorted thoughts and fears. In many of his films, this inability to see eye to eye with other human beings - even on an entirely intimate level - leads his characters to seek solace and escape; creating their own limited psychological space and projecting it outwardly in an attempt to remove themselves from the harshness of their true surroundings. Alongside these particular ideas, there are conflicting issues presented by Bergman in other films, for example Persona (1966), in which the outward projection of an idealised world that protects you from the judgements and criticisms of the wider world is internalised; giving way to a breakdown in reality and the projection of various visions that have no clear bearing on the truth. That is what this film is about.Here, we have the idea of war presented as a literal nightmare; with two characters at war with one another and at war with themselves, and all further represented by a landscape of cold uncertainty, violence and turmoil. With this in mind, Shame (1968) is perhaps not the easiest Bergman film to appreciate, though it is one of the most fascinating; especially when we compare it to the similar elements presented in the subsequent film, A Passion (1969). As with that particular film, Shame offers a story about characters in retreat; in retreat from themselves and from the world around them. In Shame, the idea is given further dramatic weight by an approaching civil war set to eventually destroy the walls of cowardice and self-preservation that these particular characters have put up to protect themselves from the harsh realities of life. As the walls begin to tumble, the two characters begin to show elements of their true selves that they have hidden during the idyllic years spent safely hidden away on the island, and the escalating horror of the world itself becomes secondary to the crippling emotional suffocation and psychological breakdown of the characters.There are a number of other, more complex themes analysed alongside this central idea, with the typical Bergmanesque issues of jealousy, adultery, guilt, impotence, lack of communication and the inability or unwillingness to see the world for what it truly is. The film is naturally outstanding on a superficial level; the production design, editing and cinematography are harsh and gritty, the performances from all involved are honest and enthralling, and Bergman's carefully detached presentation of the script lends itself to some truly harrowing sequences that manage to sidestep any potentially fatal moments of melodrama. The film is also notable for what seems like an increased budget - or at least, increased by the standards of many of the filmmaker's more iconic chamber-pieces - with Shame featuring aeroplanes spitting machine-gun fire and shells across the tiny island community, a procession of military vehicles stretching back through a small Swedish town as far as the eye can see, thousands of extras, explosions and costumes, all establishing this callous and nightmarish world that seems to exist without time and context.The fact that Bergman chose to leave the setting of this film a mystery is one of its most interesting aspects. Although the threat of civil war and some of the more heart wrenching depictions of abuse and degradation might suggest the era of the Second World War, the cars and costumes and central ideologies are all very much a post-war, 1960's abstraction. No information about the war is given, other than the fact that it has split the country down the middle (though again, the country is never specified) and both sides seem to be using a regime of violence and threat to manipulate the locals into assisting in their cause. The fact that the war is seemingly secondary to the war that erupts between the two central characters is again a sign that Bergman is using metaphor to externalise a very much internal story, with the inner-battle between two characters being projected out, against the landscape, and resulting in further elements of interpretation that set the scene for Bergman's subsequent film, the tortured masterpiece A Passion.At the end of A Passion we have a vague and enigmatic scene that not only contextualises the whole of that particular film - and its two central protagonists - but also the whole of the film in question. Quite what Bergman was suggesting by this odd sense of duality is ultimately unknown; however, I can only suppose that it points towards something of a dissatisfaction with Shame and its overall intentions; with Bergman feeling the need to clarify his own purpose with that subsequent film. Was he unhappy with Shame? Did he feel the story became lost in the superficial qualities of production design and special effects? Or that the political attack and its subtle comment on the mechanics of the Second World War were too sharp? Who knows? Admittedly, the sense of abstraction here is understated more so than in many of Bergman's other films, for example, Hour of the Wolf, which used elements of horror and supernatural iconography to underpin the story of an artist driven mad by personal demons and ghosts from the past, but I feel that Bergman is clearly attempting something similar with this story of two seemingly mild-mannered, pacifistic musicians discovering darker shades of their personalities when threatened by the approaching war.With this in mind, there are the obvious themes of dehumanisation, as the wheels of war destroy everything including the human spirit, but I'd imagine there are even deeper themes than that; something that is perhaps only truly felt when we watch the two films together, and see Bergman's perhaps cruel mocking of his characters, and the subtle line in which one painful nightmare bleeds into the next.

View MoreThis is one of the bleakest, the most harrowing of Bergman's films I've seen. I also think this is one of the most powerful films about the ugliness of war and what it does to the human souls.The couple of musicians, who left a big city for a remote island and make a living as farmers, find themselves capable of unspeakable and shameful acts that would have ordinarily been impossible for them even imagine, as they struggle to survive horrible reality of war. They betray their souls, their friends and even each other in a desperate attempt to simply survive another day. Liv Ullmann and Max Von Sydow are brilliant as usual as lost, confused, and terrified couple that got caught in the midst of a civil war.9.5/10

View More