Too many fans seem to be blown away

What a freaking movie. So many twists and turns. Absolutely intense from start to finish.

View MoreThis is a small, humorous movie in some ways, but it has a huge heart. What a nice experience.

View MoreThis film is so real. It treats its characters with so much care and sensitivity.

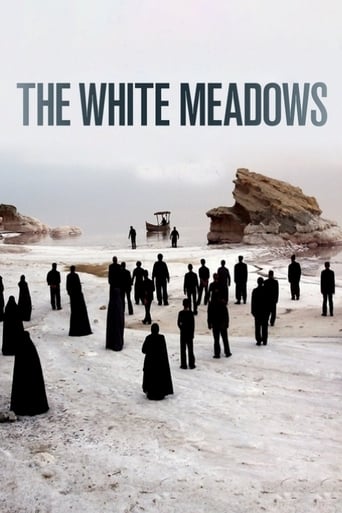

View MoreShot on the islands of Iran's Lake Urmia, an area known for its salt formations Rasoulof's mythological, folkloric allegory is as mesmeric to the eye as it is to your soul. A film that people certainly love to look at as an allegorical allusion to the current socio-political state of Iran (specifically near the end of the aughts and into the teens), is much more, thanks to the intentional ambiguity of Rasoulof who keeps his symbolism obscure enough to avoid pretentious critics like me, as well as Iranian censors, but never obscure enough to ruin the film. Rasoulof and cinematographer Ebrahim Ghafouri's humanistic eye and poignantly subtle plot deftly avoid "artsy" vagueness as well as the staid burden that a "political" film can bring, thus effortlessly bringing about a film that touches something universal, while staying complex in its folk-riddles, simple in its sorrowful tales of the variations of the human condition, and cinematographically awe-inspiring in Ghafouri's use of the natural landscape to create a world only half-rooted in reality. The ethereal sense the film is given by the landscape: the mist, the water, the reflections, the dull white salty islands which all blur the line between foreground and sky, eliminating the horizon creating a duality of possible existences is essential to Rasoulof's myth creation. A result that is reminiscent of Theo Angelopoulos. The film centers around solemn, professional Rahmat (played excellently by Hasan Pourshirazi) who rows his skid from archaic community to community, collecting the tears of the sorrowful, who are shedding their tears for one reason or another, calmly bearing witness to different rituals, practices, superstitions and tales of the lake's unexplainable rise in salinity. One of the central ambiguities is why Rahmat collects the tears—no one seems to know. His first stop is an island where a young attractive girl has died. It is implied that she was murdered. It is remarked by one of the men that she moved her body in such a way, too beautiful to live among them any longer. Rahmat collects the tears and is asked to take the body of the girl and dump her into the depths of the lake, because her beauty and sexuality is so strong that they are frightened that the male members of the community will dig her body up and violate her. Rahmat agrees and after rowing far enough away from the island curiosity gets the better of him and he wants to see how beautiful the girl really is, but as he uncovers the shroud he finds a teenage boy, Nassim (Younes Ghazali) that is a very much alive and just as frightened as Rahmat. Nassim begs to come along with Rahmat relating to Rahmat that he only wants to find his long lost father. Rahmat relents vehemently, until Nassim threatens to tell the islanders that Rahmat wanted to steal a peak at the dead girl. Rahmat agrees only if Nassim pretends to be his deaf-mute son, so as not to make the other community of islanders distrust Rahmat who has been collecting tears of the sorrowful for thirty years. In one village a dwarf Khojatesh (Omid Zare), is reluctantly weighed down with glass jars filled with the townspeople's woes and secrets. The legend is that the jars must be delivered to the fairy at the bottom of a well just before sunrise, but when the townspeople in full chant realize that Khojatesh will not make it back in time they cut his rope and drop him to his death. It is really at this point where one becomes exceptionally impressed with Rasoulof and the way he depicts these people, not with vitriol and condescension, but with an objective humanitarian eye, which is refreshing and the only way that the film can succeed in the ways that it does. On another island a young virgin is made a "bride of the sea" and is ritualistically sacrificed to the ocean. She cries and screams, begging Rahmat to help, but he cannot interfere, but Nassim, tired of standing by tries to save the young girl to no avail. He is caught and nearly stoned to death; it is only through Rahmat finally becoming active in the events around him that saves Nassim from immediate death. The ending, which will not be spoiled, is as mystifying as the beginning, while Ghafouri, through emotionally expressive close-ups or long shots of Rahmat's boat slowly rowing across the mysterious waters like some odd version of the River Styx, or of mourners discernibly dotting the white salted islands maintains the beauty and ghostliness in every composition up until the credits roll, all on a limited budget and sparse palette, never failing to aid in the mythological language Rasoulof has so meticulously but naturally created amongst the misty waters connecting all the peoples of the salt.

View MoreLast year at the San Sebastian Film Festival, Mohammad Rasoulof, Iranian director of the allegorical fable The White Meadows, spoke out against the Tehran regime saying "I come from a country full of contradictions and suffering, where there is a dictatorship," and "censorship does not allow me to talk openly about what happens in my country." The following March, both Rasoulof and world-acclaimed director Jafir Panahi were arrested as part of the government's reaction to those claiming that the election of President Ahmadinejad in June 2009 election was a fraud. Rasoulof was released shortly after his arrest in March but Panahi remained in prison until the following May.The White Meadows, Rasoulof's mesmerizing and poetic film about an old man who travels to places of sorrow to collect tears, appears to be a disguised attack on the perils of religious dogmatism, though it also can be taken simply as a surreal Kafkaesque nightmare. Set in Lake Urmia close to Azerbaijan, Rahmat (Hasan Pourshirazi), an aging boatman, visits the region's white salt islands to collect people's tears in a glass vial. "I've come to listen to people's heartaches and take away tears," he says as he rows among the gray waters in the third-largest saltwater lake in the world. It is an otherworldly landscape.Rahmat encounters many tales of grief and sees many injustices but he is powerless to intervene. He has been doing this for thirty years and the people cooperate because they believe that their tears will turn into pearls. What he does with the tears is not fully explained. We see him first at a funeral for a young woman whose body was preserved in salt until Rahmat can take her off the island and dispose of her body. It is not clear how the woman died but the implication is clear that she was killed, possibly by stoning, by having too provocative a figure. One of the villagers tells Rahmat that it was good that she had died because she was "too beautiful to live among us". She could not be buried on the island because lustful men would dig up her body and violate the corpse.When Rahmat takes her in his boat, he uncovers her far from shore only to find a very much alive teenage boy, Nassim (Younes Ghazali), who snuck off the island so that he can look for his father. Rahmat first throws young Nissim into the cruel waters then relents and says that the boy can go with him if he pretends to be his deaf and mute son. Recalling that tears can turn into pearls, the naïve youngster steals a jar full of tears and is severely reprimanded by Rahmat when discovered. At the next island, a beautiful young virgin, dressed for a wedding, is offered as a bride to the sea to appease the sea gods. No one does anything to stop this barbaric action and Rahmat is content to fill up more vials of tears.At the last minute Nissim swims out to sea to try and rescue her but he is intercepted and brought back to the island to be stoned by the elders. Rahmat saves his life but the boy is severely injured and once again the powerful succeed at the expense of the compassionate. On the next island, a crippled dwarf (Omid Zare) is chosen to deliver the secrets of the villagers (whispered into a glass jar) to the fairies at the bottom of a well before daylight. Fearing that he will not make it in time, the rope is cut and he perishes. An even more bizarre occurrence takes place at the next island. The White Meadows is an upsetting film filled with many tears, but it is a film of stark visual beauty aided by the powerful imagery of Ebrahim Ghafouri's camera-work. The film makes a strong statement about the need for morality and justice.

View MoreA salted symbolism seems to evaporate off the screen in Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof's "The White Meadows". Rasoulof, who wrote, directed and produced "The White Meadows",is closely associated to the Iranian New Wave Movement of Cinema. The film was awarded the Krzysztof Kieslowski Award for Best Feature at the 2010 Denver Film Festival."The White Meadows" was edited by one of the Iranian New Wave's most prominent figures, Jafar Panahi. Along with "The White Meadows" cinematographer Ebrahim Ghafori, Rasoulof and Panahi were arrested by Iranian authorities on March 1, 2010. In this review of the film, there is just no way for me to tackle the complex web of issues surrounding Iran's oppression of its artists.That said, as with several Iranian films, the suppressed freedom to express art and ideas in Iran hold an elemental place in "The White Meadows". Rasoulof's tale goes beyond the neo-realist qualities so often described in Iranian New Wave Cinema. The film is vividly real in its humanistic portrayals and natural landscapes, but under the folkloric lens of Rasoulof, Panahi and Ghafori it drifts into magic-realism.

View MoreI saw this recently at the Vancouver Film Festival, and was blown away. The visuals are stunning, and the characters interesting. Of course, there's a lot of symbolism that went over my head - hopefully others will explain here in later reviews.The final scene is an enigma wrapped in a riddle. Who is the old man, why are his feet washed, and wasn't the young woman pushing the chair the virgin who was sacrificed earlier? Also notice the painting on the wall, with the red sea.For those with an open mind, this represents the best aspects of International, or "foreign" cinema.

View More