It is a performances centric movie

Fun premise, good actors, bad writing. This film seemed to have potential at the beginning but it quickly devolves into a trite action film. Ultimately it's very boring.

View Morea film so unique, intoxicating and bizarre that it not only demands another viewing, but is also forgivable as a satirical comedy where the jokes eventually take the back seat.

View MoreI enjoyed watching this film and would recommend other to give it a try , (as I am) but this movie, although enjoyable to watch due to the better than average acting fails to add anything new to its storyline that is all too familiar to these types of movies.

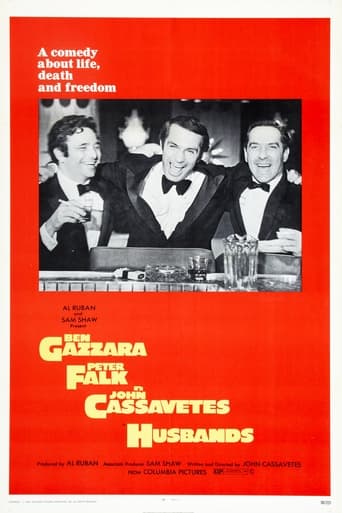

View MoreCassavetes' Husbands is at times exciting, at times funny, can a bit boring and authentically real in dealing with its three central characters, played by John Cassavetes (Gus), Peter Falk (Archie), and Ben Gazara (Harry).The opening scene where they go to the funeral of their friend - who died in his forties or a heart attack - and their subsequent all day and night drinking binge usually would give us some clear insight into these characters. Typical movies would have one of them state about making up for lost time, and the feeling they have for their lost friend. It sort of happens in the movie, but not stated so obviously. Each of the three men act out on a childish whim, and never really express themselves to each other underneath their male posturing and childish antics. In the bar scene that follows, they get into a drinking game and everyone sings (the wake where everyone shares something positive about the deceased is skipped). After Gazarra's theatrical singing, a woman starts to sing, but is berated by him to sing with more passion. This goes on for a very long time, and then his friends go on to belittle her and bully as well. The scene is prolonged to go from funny to uncomfortable and back again, but our sympathy for the characters never permanently changes. The reasons why characters act out is never clear in the movie to us, and I don't think to them, either. You cam never tell when the performers are being genuine or playing "roles" around each other. When the three are in the bathroom, throwing up in the stalls, Gazarra shows some vulnerability, but then ends up yelling at his friends, the other two not really listening. He calls them out on acting like children later on, but hypocritically acts that way himself. We don't see Gus' wife in the movie, or Archie's. Harry's wife is divorcing him, and their separation could be the source of his occasionally anguished strife. His fight with his wife and mother in law over wanting to see his kids is raw and earnest, but also a little ridiculous.Most of the scenes follow this trend of muddled uncertainty, which can leave the viewer exhausted from having to be around these three men who seem incapable of articulating themselves without damaging those around them. We don't judge them based on the filmmaker's point of view, we just observe (like a documentary, but without the imposition of trying to tell a story)."Husbands" is a demanding work, but rewarding for the virtuosic acting from the ensemble cast. Just don't expect any resolutions or neatly expressed ideas.

View MoreI'm tempted to review this as two different movies, not because the film's different acts don't flow into each other naturally, but simply because the first third of the film is, I think, so superior to the rest. The first forty minutes or so of Husbands (of the shortened version currently available on DVD in the US) is as fine, if not better, than anything else Cassavetes ever made. The funeral sequence and that at the pub with the singing of songs, is brilliant cinema. The shadow of death and loss is palpable, and the sense of drunken overcompensation can be felt by anyone who has ever, well, overcompensated through drinking. I do not think of Cassavetes as a great visual filmmaker, but some of the compositions in the bar room scene made me think of Rembrandt, with its dark hues giving way to such revealing faces. That these heads are confronted with, what in the composition amount to, disembodied hands makes this seem like Rembrandt in the age of surrealism. Regrettably, after these magical 40 or so minutes, the film then degenerates into all that I think worst about Cassavetes's oeuvre. The crudest male bonding is celebrated as liberational. Indeed, one of the most grotesque of patriarchal tropes gets wheeled out: the woman who gets abused by a man and then falls in love with her attacker. (That the perpetrator is played by Cassavetes himself makes this seem all the more off-putting.) The last couple of scenes are a memorably bleak portrayal of American suburbia, but this is compromised by the fact that we are only allowed to identify with the supposedly "put-upon" masters of this world: the white patriarchy.

View MoreHere, I continue with Cassavetes and my look at presence and jazz time. I think this can only work when you see it a second time. I have to feel like I know these people as well and deep as they know each other. And know them long enough for their quirks and peculiarities to stop annoying and become part of the damaged self I embrace in the life and time that we've seen go together. In fact, I think the film is structured in two halves for a reason, the first half so we can know them at some length, and the real film is the second half once they land in London. The idea? A fourth friend has died as the film begins, but death, how we treat death, is a formal, symbolic rite empty of life. And they can't go back to their wives, that'd be the same as every other day. It can't be either the formal or everyday time, it has to be a moment extended in time with a bit more clarity. Here we're looking to have transcendent insight. So they basically go out because that is the only way. They get drunk, sing with others, snigger and run in the streets, tease and grab and abuse each other and strangers. As I got to know them, they were all three annoying to me. Jackasses. They're not cute, nor noble, nor particularly idealistic or smart about anything; this isn't a Woody Allen film. They're not even your average guy on the street, if such a thing exists. Here's where Cassavetes' limitations kick in and the film all but loses me. He was an actor first, grew up artistically in the Actors Studio. We know the school as going for a natural embodying of character after Brando and the likes, but its actual roots are Soviet and go back to constructing room around a self. A Studio actor's job is to go into that room and toss the furniture, tear at the walls a bit. What we see here are three actors, all very good ones, all lovable in other projects, deeply immersed in trying to construct the fact they are not acting. They are, we can tell. It's an alienating effect, because they expect us to not know it's feigned. We want to not know, because that would be tearing through their craft, but the scaffold is all there. They mechanically repeat lines and pause for effect, they act manic and loud all the time, they come up with artificial small talk and repetition; it's all a bit off, calling attention to the eccentric, actorly tearing of wallpaper.If that were all, I'd rate this low, there's just nothing particularly useful to me about this ideal of realism. I'd much rather have nonactors. But there is something else— let's say time and consciousness. It's not different in tone once they reach London, but something happens. We already know them. Now we know them as other people are getting to know them, mostly girls. We know them as friends know each other in a crowd. It's a strange and slow effect at work, because it works against what we knew of them so far—away from home, they're a bit more lonely and desperate. Is the zest of connection more real now, next to strangers? Strangely, it begins to work and that changes everything. We have memories of having spent time. Look, many great works are this way, split in two parts which are time and present consciousness of that time —Lolita, Vertigo, Mulholland Dr. Time is never a lone abstract, there is no yesterday outside where you were doing what you were doing. It is rooted in space and self so we conjure all three in memory, we always do. It is a film about the memory of departed friends, but it's all in the fabric of our experience. It plays against a larger void, the one where eager, mysterious London girls come from, there they are in the room and gone again. The transcendent insight is, of course, that there is only now and the place you are, but that space of mind is always loaded with the consciousness of having known everything else, jazz time in constant improvisation.It's a strange and difficult experience, because as in life, the larger point becomes apparent in reflection. It may be a film that'll stay with me for a long time, getting better in memory. But is it an important cinematic step? Of course!

View MoreThe very first bit of dialogue is the kind of introductory exposition you get and gradually learn the rhythm of from a movie that is testing you. Being a film by John Cassavetes, it shall be one of those films that leaves you unsure of what to think of it at all, except that you were strangely engrossed in many scenes, only not quite like other examples of this sort of movie experience. His sense of pace is epic, but the subjects that fascinate him are granular in scale. Husbands is a Cassavetes film that even experienced Cassavetes film watchers aren't quite prepared for. It is a formalistically rebellious, gravely intimate reflection of the bareness of suburban life, magnified 500%, unpatronizing to and violatingly honest about its anxious, inarticulate sticks in the mud who have no idea what they're feeling while they're undergoing their feelings.The dialogue is comprised of unfinished thoughts, of knee-jerk shouts, not to mention three actors with egos more massive than the movie's gaps of seeming inertia. The camera just rolls and the microphone just hears. That we're seeing and hearing anything in particular is not as central as the fact that we are indeed looking and listening.Cassavetes tries so hard to seize and squeeze every possibility of any moments that catch what we all know happens between concept and execution. Moments that don't seem scriptable, that hardly seem describable. When we're with somebody but before anyone's thought of anything to say, or when we are distracted into an unthinking transition, anything impulsive or seemingly without thought. I might even go so far as to say the whole film seems involuntary. And what's more, it is predominantly comprised of Cassavetes' trademark scenes of agonizing discomfort.The most emboldened stand-out in this film's succession of scenes of that nature is an inordinately long one in which Cassavetes, Gazzara and Falk sit with a table of friends and family in a bar, not a tissue of their body left dry of alcohol, taking random turns singing traditional folk songs, and after awhile---and I mean awhile---one person begins singing, and the three jeer them into silence, then tell her to try again. They jeer her quiet again, and again and again and again until finally, after anyone in her position would still be cooperating, they praise her for finally getting it right. This to me represents what has to be the creative process for actors in a Cassavetes film, especially the Cassavetes film Husbands. There seems to be no frontal lobe left in any actor.Husbands is described sometimes as a comedy. Well, I don't know if it's a comedy, but is a drama with sporadic moments of strange, seemingly incidental humor. There is an unusually brief scene where Gazzara visits his office and is greeted by an outlandishly goofy colleague. When the three friends are electrified with excitement about going to London, we cut to London, where it's dreary and pouring rain. There doesn't seem to be a way to pinpoint the nature of the movie's tone, or its structure at all. Like I said, it puts you to the test, and the test is to accept the film on its terms. If you do, you can be moved by the nature of its point of view and be open to the nature of your own reactions to it.

View More