one of my absolute favorites!

It was OK. I don't see why everyone loves it so much. It wasn't very smart or deep or well-directed.

View MoreThe movie's neither hopeful in contrived ways, nor hopeless in different contrived ways. Somehow it manages to be wonderful

View MoreThe film's masterful storytelling did its job. The message was clear. No need to overdo.

View MoreIn the movie, the writer/producer fails to point out that the sale of YUKOS OIL's assets and other assets sold to the oligarchs was a move by Yeltsin to protect the Russian economy from being "owned" by business outside Russia. If the assets placed in the auction had been offered for their true value, only large corporations outside of Russia would have been able to afford them. In order to have them owned by Russian businesses, they were offered for rock bottom prices. Only a few business people in Russia had the assets to acquire businesses such as Yukos. Whether it was "stealing" from the Russian people is a moral question that is difficult to answer since the practical reason for the sales was so complex. Prior to the sale, the government owned all the assets, so did the government "steal" from the people by controlling all the assets? Did the government provide its citizens the benefits of those resources, or did government officials plunder the assets, too. According to continuing reports from analysts who study Russian politics, Putin has amassed a fortune estimated at $60 billion during his terms in office. Did he acquire those assets through corruption or legitimate means? At least when business people own assets, the people they employ benefit by receiving a salary. In the U.S. the discrepancy between what CEOs earn and what the average worker earns represents a gap of about 475%. Some people in the U.S. view CEOs as "stealing" from the shareholders. If the documentary had presented some of these facts so viewers could see that this is not a "black and white" issue, the movie would have provided a more substantive explanation of what happened during the 90s and how Russia and Khordorkvsky changed - from a country that had begun to move toward democracy to one with an iron-fisted leader who appears to be as corrupt as most Russians view Khordorkvsky. As a documentarian myself, I know it is difficult to present this complex subject in a brief and interesting film. I do think the writer/producer tried because the movie talks about Khordorkvsky's taking advantage of the "system" which at the time was totally legal when he bought Yukos to the Khordorkvsky who was supporting the opposition movement. Whether he was doing it for political gain (wanting to be president), I doubt. Recent events show that was not the case. His public statement that the president needed to do something about corruption viewed as the catalyst for his arrest indicates that he was attempting to present his new-found capitalistic business approach as a better way for Russian to operate - to attract foreign investment. Whether it was arrogant of him to speak publicly to the president is an open question, but in the U.S., people challenge the president constantly to "fix" what's wrong with the country. One has to decide - was Khordorkvsky being arrogant, or was he operating under the assumption that government can affect changes in problems facing the country as is expected in a democratic country?

View MoreThis piece of Michael Moore-esque propaganda (with the same kind of whiny, sentimental voice-over) is an absolute load of nonsense.Most Russians know Khodorkovsky as a crook, a bandit and a criminal who made billions from stealing natural resources from the country during the chaos and lawlessness of the 80s and 90s in Russia. Cyril Tuschi's attempts to portray him as a martyr for freedom and democracy in Russia is disgusting. The nods towards a more balanced account are distinctly feeble: quoting Khodorkovsky talking about breaking 'ethical standards from today's point of view' (no s**t), the former Yukos lawyer talking about Khodorkovsky helping create the very system that condemned him, relating his possible connection to the killing of the mayor, quickly dismissed by the next interviewee: 'I hope. I am almost certain, that (he) wasn't involved in this. I have serious doubts about some other Russian oligarchs'. Why does he hope and what makes him almost certain? What's his evidence that one of the most successful oligarchs wasn't while many others were? The film never interrogates this point. Khodorkovsky paid just $309 million for Yukos - in an auction held by his own bank - by 2003 it was worth $45 billion. This was hardly down to Khodorkovsky's management genius. No one got that far in that period in Russia (and in so short a space of time) without doing the worst possible things to get there. If practically everyone was doing it, how did one of those who was most successful in that era stay largely clear? Just so you are under no illusions as to Tuschi's agenda/viewpoint in this film, I'll give you a few quotes from an interview that he did with Spiegel Online. In it Tuschi asserts that 'I am an artist not a judge', who is merely 'presenting an interesting film about a unique person', but in response to the very next question says that 'he has an almost transcendental, supernatural aura. It is the aura of a martyr'. This film is clearly the portrayal of a hero (albeit a flawed one, as the best heroes are!) - just look at the moment when Tuschi finally meets Khodorkovsky and shakes his hand in awe, and the suggestion earlier in the film that Khodorkovsky's earliest thinking, and his core, was and is influenced by the populist ideals of 'Pavel Korchagin', fighting for the good of the people, 'for the people's liberation'. To compare Khodorkovsky to the fictional Korchagin, as Tuschi is clearly doing, is a laughable disgrace. Khodorkovsky cares nothing for the well-being of the Russian people. Until he had political ambitions (again for personal gain), for which he was imprisoned and his assets seized, when did he give two cents about the Russian people or democracy? All of those years of raking in money at the people's expense. He was a crook amongst crooks who lost out in the power struggle, nothing more. The attempts by people like Tuschi (or The Guardian in the UK) to turn him into a martyr in Russia's struggle for freedom is pathetic. The film is too busy fawning over Khodorkovsky to provide any insight at all into the nuance and detail and context of what is going on. Tuschi came and went with the same lazy preconceptions about Khodorkovsky and his role in Russian society and he expects us to do the same. He seems to blindly accept what his interview subjects say, subjects who are almost exclusively former and current associates of Khodorkovsky. He also employs Michael Moore's patented technique of bursting in on officials unannounced, demanding they answer difficult questions on the spot, then instantly interpreting their refusal as them evading him because they have something to hide.Here are a few particularly egregious snapshots of how idiotic this film gets:in a weird and creepy black and white animation, he has Khodorkovsky swimming across a swimming pool of gold coins towards a sign that says 'Open Russia'.in an interview, Leonid Nevzlin, a multi-millionaire if not billionaire former Yukos executive in exile (who, poor guy, complains of all the sunshine in Israel), has the cheek to say: 'We need some money. We need compensation. Not because we don't have money, fortunately we saved some money, but because they stole a lot of money, our part of Yukos oil company. So why we should forgive them for this? They should pay.' The film makes no mention of the irony of this. The Russian government's seizing of assets is repeatedly commented on and yet no mention is made of how (and in what context) the Yukos managers made their money in the first place.the melancholic footage and voice-over of the now largely empty 'Yukos Compound' with its massive walls and mansions. 'Five of seven manager's houses are empty. Otherwise only the employees remain, who keep the park and pool in order, heating the empty houses and sweeping a garage for 50 vehicles that now stands empty too'. Need I add anything to his own words? Is Tuschi listening to what he's saying here? What exactly is he mourning for god's sake? Yukos' former lawyer complaining about the state 'tricking the oligarchs the oligarchs - they got no rights.' Lets all weep for the injustices suffered by the poor billionaires when the Russian government reasserted its authority after they had made so much money by opportunistically grabbing at a cut-price any industries that were lying around after the collapse of the Soviet Union. You know who had no rights? The ordinary people who were left with a disintegrating state plundered by bandits, whose savings and pensions were repeatedly wiped out, who lived in abject poverty and chaos while people from the Yukos cartel (amongst several others) drove by them in their black Mercedes with tinted windows and appropriated police sirens.

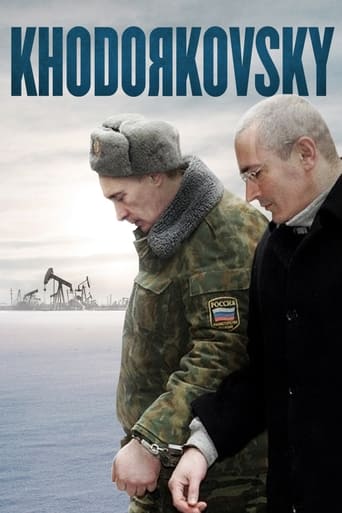

View MoreIn 2003, Russian oil magnate Mikhael Khodorkovsky was arrested on charges of fraud by the Putin government. The owner of oil giant Yukos, one of the largest companies to emerge from the privatisation of Russian state assets during the 1990s, Khodorkovsky later had a prominent and public role as a financier of the Russian opposition in the 2000s. Quickly found guilty, the oligarch was sentenced to nine years in prison, later extended to twelve. From prison, Khodorkovsky has waged a campaign in Western media to raise awareness of the injustice of his incarceration and the corruption of the Russian political system that permitted such a turn of events.Cyril Tuschi's 'Khodorkovsky' is part-biopic, part-criminal investigation, seeking to uncover (against substantial odds) both who the real Khodorkovsky was and whether his well-publicised trial was political posturing on the behest of Putin or an accurate reflection of the murky dealings of the Russian oil industry - an industry borne out of the questionable auctions of the Yeltsin government in the 1990s. Khodorkovsky, in a manner similar to his fellow oligarchs, acquired Yukos in 1995 at one such state auction, paying well below the market value. Soon acquiring a reputation for being a perennial corporate governance abuser, Yukos (and its billionaire owner) underwent a volte face at the turn of the millennium. As it's transparency began to encourage immediate investment. the share price saw a swift upward turn. Simultaneously, on the advice of an American PR firm, Khodorkovsky launched "Open Russia', investing $100 million in Russian education projects. By 2002, Khodorkovsky was both the world's richest man under 40 and the symbol for sound civic governance in a Russia still blighted by corruption and inequality.Though rich and powerful enough to brush shoulders with the oil magnates of the world, Khodorkovsky's mistake was to take that attitude, that perceived arrogance, and impose it upon a Russian political elite not yet ready to accept their subservience to the new business elite. Specifically, Khodorkovsky butted heads with Putin, ignoring the President's plea for the select group of oil oligarchs to stay out of state politics entirely; associating himself closely with the opposition to Putin's iron-fisted rule, Khodorkovsky emerged as a powerful motor to the campaign offering a increasingly popular alternative. His days were numbered.Though no saint himself, Khodorkovsky's arrest and incarceration emerge as a representation of everything still wrong with Russian politics. The cronyism expected of the Russian oligarchs in return for ease of operation betray the long road left to transparency, for which Putin remains a sturdy barrier. For as long as he remains behind bars (and Putin remains in power), Khodorkovsky may question his decision to return to Russia (many others sought exile around the same time), but there is hope that he will use the experience to justify a run for office once released. Until then, he waits.Concluding Thought: Brilliantly paced. Difficult, complex topic rendered manageable.

View More