Self-important, over-dramatic, uninspired.

ridiculous rating

Don't Believe the Hype

What a freaking movie. So many twists and turns. Absolutely intense from start to finish.

View MoreA viewer can expect a lot in terms of action and plot from a film about a prisoner who has been released from a prison.However,there are films which give the impression of visual stories where a lot happens even though viewers are unable to make sense of those happenings.In such films,a conjuring effect is created according to which nothing seems to happen but in reality a lot of minor events are shown to happen at regular intervals in the film.It is from such an angle that viewers can watch "Los Muertos" directed by talented Argentinian filmmaker Lisandro Alonso.The ruthlessness with which two murders are committed in the beginning lead viewers to believe that mystery and suspense would be evident through the film.This belief is quickly contradicted when the film begins to concentrate more on daily life of the protagonist.The result is good for eyes but fails to fulfill the expectations of the mind.Los Muertos is not an experimental film.It is a normal feature film which any ordinary viewer would like to watch.

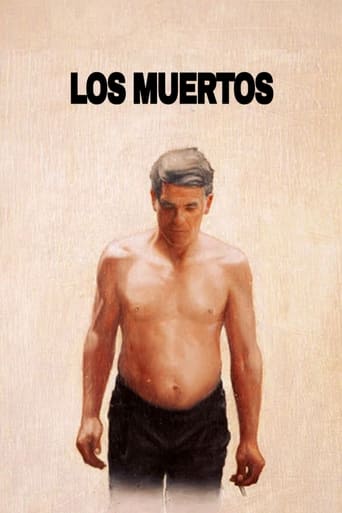

View More"Los Muertos" made me think of various things -- Hemingway, John Boorman's 1984 "The Emerald Forest," the Mexican Carlos Reygadas 2002 "Japón," the films of Bruno Dumont. This film shares "Japón's" use of natural settings and non-actors for a powerful minimalist effect. It's got the macho focus on simple survival tasks you find in Hemingway's Spanish novels and early short stories set in the Michigan woods. When "Los Muertos'" protagonist Vargas (Argentino Vargas) gets out of jail he goes into the outback He travels downriver in a rowboat with a few provisions, feeds himself from a tree, slaughters an animal and cleans it in the boat. The crowded, open prison and the shops Vargas goes to when he first gets out are busy -- "civilized." Then he enters his own "Heart of Darkness" like the boy Tomme in "The Emerald Forest" and becomes a different person -- shucking off clothes, money, possessions, bringing out new skills. Like "The Man" in "Japón" Vargas is going to a remote region on an ambiguous mission and the two movies both take long looks at the land and listens to real rural people. Like Bruno Dumont, Alonso isn't afraid of long still shots and 'longeurs,'and like Dumont his sex is crude and real. Like Dumont's, Alonso's protagonist is inarticulate and vaguely dangerous.We see a lot of Vargas at first just sitting, sipping maté, staring into space at the prison, like you do. But Alonso's camera is also lithe and mobile from that first long hypnotic panning and tracking shot in the forest before the story begins and it continues to be supple and quick as it follows Vargas on his journey.Style apart, Alonso takes us to a place we don't know and he keeps us there. He doesn't explain; his film suggests you can get very close to things and still not understand them, and sometimes that's the way it has to be.The actor, Argentino Vargas, resembles Franco Citti, whom Pasolini often used in his films for sly, evil characters. Like Citti, he has a rough, sensuous quality. He's paunchy but muscular, tan, and agile; he's a handsome man gone to seed, a little 'indio', a little worldly. He's polite and neutral with people, but there's something not said, something blank and mysterious and menacing about him too, a sense of an unexplained purpose. This man is very, very alone, and his outdoor skills outline his ability to remain that way. We don't know what he's up to. We don't know what he's capable of.This reserve, this mystery, is an essential element in much good storytelling that can make the simplest tale compulsive and memorable, which is what "Los Muertos" gradually becomes. Carlos Reygadas also uses it.Since "Los Muertos" tells us so little and there are so few spoken words, little bits of information jolt us awake and our minds race. "So you're leaving!" a young man yells at Vargas at the prison. He comes too close, then disappears as if he was angry and was pulled away -- and we may think Vargas is planning to escape and word's gotten around. But instead he gets formally released.Watching Vargas'journey suggests what travel or nature movies would be like if they had no music or commentary -- how much more powerful a camera can be without mediation, when it's just there without conventional framing devices. A long shot just shows Vargas in the rowboat, rowing on the river, coming toward us. There's nothing else. The camera is invisible, moving imperceptibly. The shot is powerful and extraordinarily beautiful and alive because it just is. There's a boldness about Alonso's method. Some shots may seem too long. But there's an exhilarating sense of really being wholly inside the experience; of having lost ourselves completely in the story "Los Muertos" tells. I got that feeling when I first watched Boorman's "Emerald Forest," and it was a strange and alien -- and at the same time thrilling -- feeling to walk out of the theater into the nighttime city when the movie was over but I was still under its spell, my mind lingering in the Amazon forest.Lisandro Alonso, who's only thirty years old, reminds us that great film-making can be a matter of letting the camera and what it sees speak for themselves. He throws out the paraphernalia. During the course of the film, we've seen and heard some surprising things. At the end, we're suddenly excluded. Vargas goes somewhere, and the camera doesn't follow him. It stops showing us what's going on. The camera has been our eyes and ears and this abrupt shutdown is a shock. You walk out of the theater and you carry that sense of shock with you. It's a brilliant ending to a haunting film.Seen at the San Francisco International Film Festival April 26, 2005.

View MoreLos Muertos is a contemplative and controlled film about men in their environment. The film is incredibly understated, but never boring, in that it is always moving. The lead character, Vargas, is simply moving towards where he wants to go, first to deliver a letter one of the inmates left behind gives him for his daughter, then to find his own grown daughter.The poetry and grace in the storytelling is in simply watching this man, who has very little interactions with other humans, move forward. He is a man of little words, and of deliberate (and sometimes startling) action. The jungle is a powerful metaphor, of course, as is the river he travels in a small boat. The details of his journey are compelling and almost hypnotic - his smoking-out of a hive to get honeycomb, his sudden grabbing of a goat on the shore to kill it (my, I wish I had been warned of this scene - it happens in one cut and is not faked), etc.An elliptical comment early on, in which a man cleaning a fish asks if he really killed his brothers, is answered by Vargas, "I don't remember all that anymore." That's about the extent of the backstory, and the film allows you to consider this man's place and if he can ever find what he's going towards. Less is more in this case, and the film-making ends up being powerful, and evoking Anonioni or Dreyer in its confidence that showing a person in his/her surroundings is sometimes drama enough.

View MoreThis is not a film for everyone. The slow pacing can easily get to the nerve of the toughest film watcher. The tale of a released convict and his voyage to reunite with his family is completely ascetic and deprived of embellishments of any kind. Still, the images are hypnotic and set the viewer in a trance-like experience. Vargas' dryness is much more interesting that the dullness of many other protagonists of the so-called 'new argentine cinema'. It is everything that he conceals us what makes us interested in him. The narrative evokes the literature of Horacio Quiroga, an Uruguayan writer who frequently used the Mesopotamian jungle as his main character. Every inch of that jungle breathes, and compared to it, every human being in the picture is the dead referred by the title. Alonso has created a fascinating piece of machinery that flow quiet and slowly like that ever-present river, despite some pointless 'contemplative' scenes that might have been included to fill screen-time. Alonso's virtue is his ability to tell a story visually this is more silent than a Murnau film-, and his film-making makes full sense in the viewer's mind. He's miles away from the pretentiousness of the director that made 'Japón', a film with which it shares a number of elements. One admires his ability to walk over successfully that thin line that divides cinema from poetic arty trash.

View More