This movie is the proof that the world is becoming a sick and dumb place

View MoreDreadfully Boring

Easily the biggest piece of Right wing non sense propaganda I ever saw.

View MoreThe best films of this genre always show a path and provide a takeaway for being a better person.

View MoreAn evil had come to the tribe and killed the leader. His ambitious son Sauri takes over. Tulimaq is the worst hunter and a laughing stock. He is ridiculed relentlessly by Sauri. His wife tells his son Amaqjuaq to always look after his younger brother Atanarjuat. The brother grow up to be the great hunters of the tribe. Atanarjuat falls for Atuat who has already been promised to Sauri's malevolent son Oki. They compete in a contest and Atanarjuat wins Atuat. Later Atanarjuat is seduced by Oki's sister Puja who becomes his second wife. Puja causes great problems by sleeping with Amaqjuaq and telling Oki and Sauri that her husband tried to kill her. There is great tragedy and turmoil in the tribe.There are some amazing stuff about the world of the Inuits. The simple act of icing a sled is endlessly fascinating. The story of love and betrayal is great Greek tragedy. It is a little confusing at times because it takes some effort to keep track of some of the characters. The main drawback is the film's inability to explain the magical significance of some of what's happening. It leaves the story a little bit muddled. However there is nothing like this in the film world.

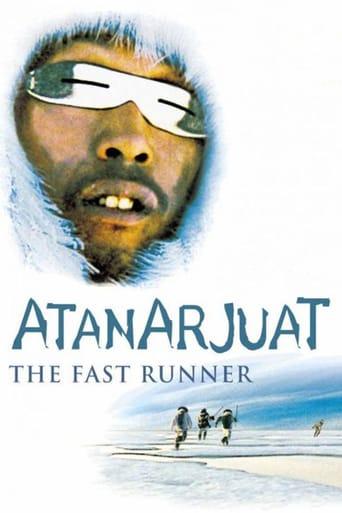

View MoreThe first movie ever filmed entirely in Inuit has a slightly convoluted plot, focusing on treachery among a group of people in the Arctic. It had the feeling of a Greek tragedy or Shakespeare play, despite taking place in Greenland (or some place similar). "Atanarjuat" - meaning "The Fast Runner" - is most memorable for showing a culture that we don't usually get to see. A few months after I saw it, I went to college, and one of my friends there remembered the same scene that I did: the man running naked across the ice.I should say that the end of the movie broke my concentration when they ran the credits and showed the crew. But for the most part, I found it to be a very impressive film. Definitely one that I recommend.

View More"The Fast Runner" is sometimes beautiful to look at, and in its immediacy it is at times able to transport the viewer to another time and place.But this is a bad film. In terms of storytelling, editing and narrative, it just doesn't make any sense. I found myself taken out of the film as much as I was immersed in it due to the poor film-making techniques.I'm sure that there are some people who were generally moved by this film, and it has a few very compelling moments. But as a film overall, I can't imagine how it gets such universal acclaim, especially considering its sub-AV Club technique. (I hate to call anyone's motives into question, but I tend to think that more than a few people who heap praise upon this film are doing so out of a need to praise this plucky group of Inuits for making a film at all. I think it's less condescending to evaluate it out of context.)

View MoreForget its awards and honours, the Camera d'or from Cannes and that raft of Genies and a bagful of other festival citations. For now, there are only three things you need to know about Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner: (1) It is a superb film; (2) It is both intriguingly exotic and uniquely Canadian; (3) Although based on an ancient myth, and set on a distant shore a thousand years ago, it speaks eloquent volumes about the way we live now. The abiding myths are like that, of course, but few movies have managed to harness their timeless power -- this movie does.The setting is the far north, that white expanse embedded in today's consciousness as a totem of all that's virginal and solitary and silent, a romantic escape from the hubbub of modernity.Well, think again. Even at the dawn of the first millennium, the Inuit lived there, and they lived through a matrix of social and political tensions that will seem hauntingly familiar -- tensions that the subsequent centuries of apparent advances and creature comforts have done nothing to change or resolve.This enduring dialectic is the subject of the re-enacted myth. Actually, the filmmakers prefer the term "relived," and with good reason. That's because, shooting on location with native actors talking in the Inuktitut language, director Zacharias Kunuk has contrived simultaneously to give the picture the realistic look of a documentary and the dream-like feel of a fable. So we're plunged directly into the daily minutiae of this other world -- its frozen geography and its igloo dwellings, its food and utensils and weapons and clothing, its little jokes and its chronic rigours. However, as the narrative gathers momentum, as the myth unfolds, its themes seep out of the recreated past and into our smug present.Certainly, the story's initial note will ring a bell. The first sequence depicts the fall of this icy Eden. If the opening appears a bit confusing, even disorienting, so be it -- what can be more perplexing than original sin? Or as the script (by the late Paul Apak Angilirq) puts it: "Evil came to us like death -- we never knew how it happened." Yes, evil -- a word that isn't exactly underemployed these days; and a concept that the myths of religion were invented to explain, and to control.The picture is mythic in content but never in presentation. These people aren't just icons in an old saga; they're living, breathing folks who belch and break wind, who giggle and flirt, who strut and posture and, between bites from a caribou steak, sing bawdy songs that embrace timely truths. (Sample lyric: "Even a big man can't bring home enough food/ If what's hanging between his legs gets too stiff.") This brand of realism is no accident. Instead, it's the long-practised method of Kunuk and his cinematographer Norman Cohn, who share an extensive background in video art, the slow-paced kind that emphasizes watching over telling. Alternating from sweeping panoramas to stark close-ups, from hunters mushing a sled over crevassed ice to a woman's gnarled hand holding a bone needle, their camera is keenly observant to both sights and sounds. It hears rhythms in the winter at its harshest (the incessant crack of footfalls on rock-hard snow); it sees beauty when the seasons change and the harshness briefly relents (a lone kayaker paddling over still waters glinting in the midnight sun).That's not to say these guys can't shift into a kinetic gear when action is called. In fact, they have the skill to animate cinematic clichés. There's a chase sequence here that's as good as any I've seen in a decade. And there's a ritualistic punch-up, black and bruised, that puts any studio western to shame. Also, as with every paradise-lost myth, the violence is paired with an ample helping of sex -- sometimes brutish, often loving and, on more than one occasion, wonderfully erotic.Naturally, a film with such a broad range demands a lot from its actors. They respond impeccably, professionals and amateurs alike. Natar Ungalaaq in the heroic title role, Pakkak Innukshuk as the resident villain, are both playing nicely rounded characters -- the one has his flaws, the other has his merits, and the performances reflect these duelling sides of the moral equation. With her flashing smile, Lucy Tulugarjuk is a delightfully designing woman, the kind of born drama queen who can somehow make even the most selfish act seem ingenuous. Finally, poignantly, Sylvia Ivalu weeps real tears as the beleaguered wife, streaming rivulets that bisect the tattooed lines on her swollen cheeks.Too often, our Western response to aboriginal culture carries a strong whiff of the sentimental, of the patronizing and the politically correct. But Atanarjuat steadfastly resists that. Rather, it demands both to be heard in its own voice and to be appreciated on its own terms -- not as a quaint native artifact, but as a damn fine and a truly distinctive and a deeply pertinent film.That pertinence is no more apparent than during the resolution, where the myth offers up its answer to the troubling riddle of evil. Only when the Fast Runnner slows down can he reach, and understand, his epiphany. Significantly, it comes before the practical matters -- and this is a practical society -- of meting out punishment and tempering justice with mercy. More important still, it comes from a man wielding power at the business end of a knife, and it wells up as a cry from the depths of his anguished heart. Bold, brave, direct, decisive, the cry doubles as an assertion, cutting through the clamour of the centuries and their cycles of violence, cutting through all the unholy dins in all the holy lands. Shouted in an ancient tongue, his four words speak to every age, none more forcibly than our own: "THE KILLING STOPS HERE." Benjamin Miller, Filmbay Editor.

View More